When Julie Hedlund asked me to join her and Mary Hoffman as a faculty member for her 2nd annual Women Writers’ Renaissance Retreat, she set me the following the task:

I want you to teach us what you do. What you did, for example, in Beware Madame la Guillotine to make Charlotte so real that she seems to speak to us directly from the grave.

The theme for the Renaissance retreat would be “writing from a sense of place.” Our backdrop: Florence, Italy.

I said "I'll do it!" Wouldn’t you?

Ever since, I’ve been on a personal quest to understand what exactly my writing process is -- specifically for developing stories for Time Traveler Tales & Tours -- so that I might well explain to others.

Start with a Sense of Place

Along the way, I’ve tapped into my primary sources: authors much wiser than myself, such as Mary. Though she and I work in slightly different genres -- historical fiction and creative nonfiction, respectively -- it turns out we share a similar jumping off point.

We start with a sense of place.

We research our focus era like crazy. We steep ourselves in the setting and time of our eventual stories. We read everything we can get our hands on. We visit. We talk to others who know about it. We visit again. We start broadly with secondary sources; then drill deeper with primary ones. We look for the holes in the research and seek to fill them. We chip away at our metaphorical blocks of marble, until our characters emerge. Because it’s in truly knowing your place that your characters might then rise up to tell their tales themselves.

A few of Mary's historical novels found in the local English-language bookstore.

Add Character...

Now that we're all in Florence and following Michelangelo's footsteps, I'm reminded of his process of carving the David. As I learned from Mary’s book of the same title (a must read, BTW), Michelangelo had tripped over the same discarded block of imperfect marble for years before winning the commission that would allow him to carve his famous statue.

He’d already studied the block, kicked it, drawn on it, smiled at and frowned upon it. He’d made many sketches and changed his mind several times about the character the stone contained.

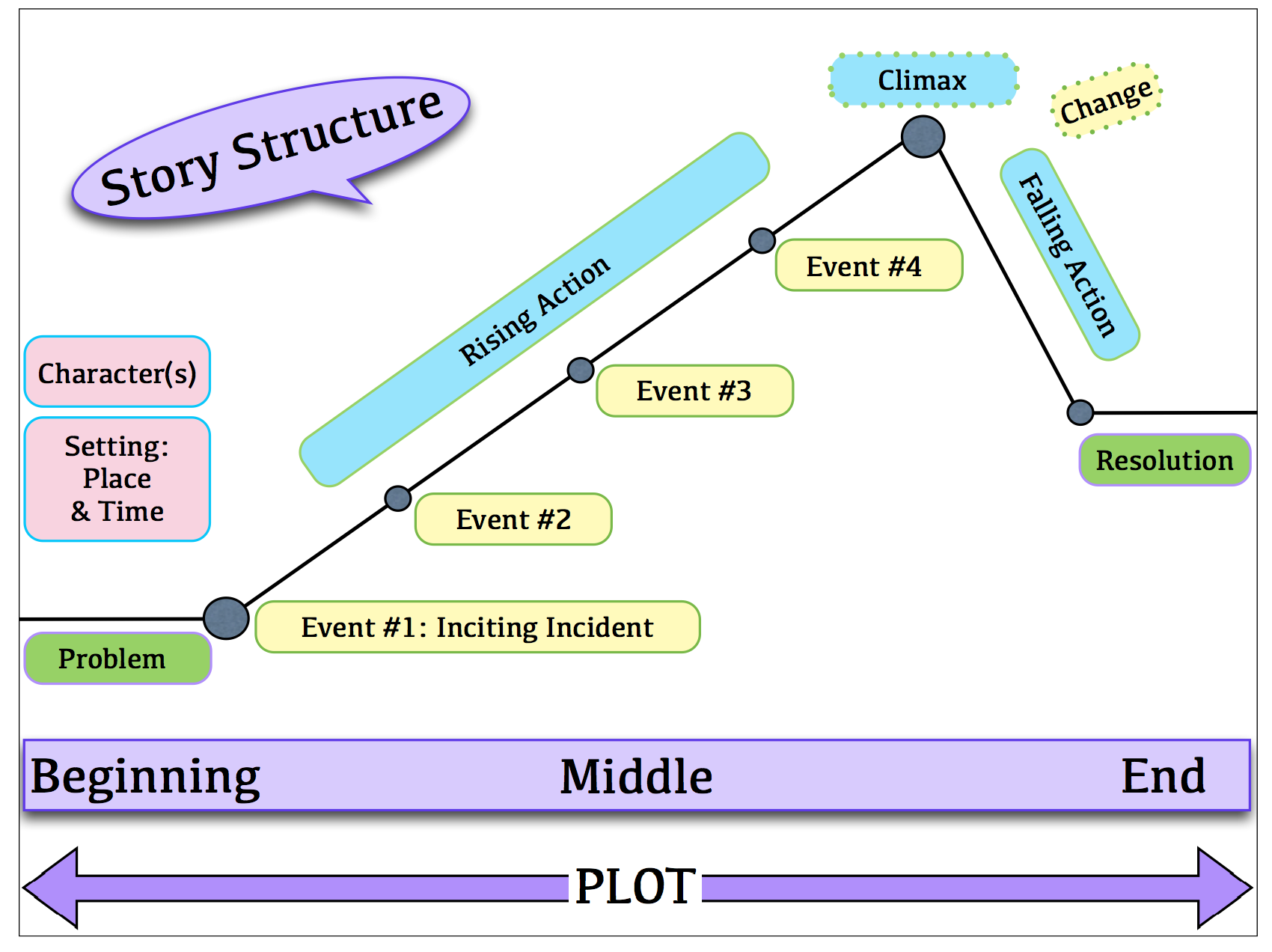

...and a Dash of Plot

Likewise, when Michelangelo was finally ready to pick up his chisel and hammer to strike the first blow, he was certain there was a story hidden within. He only had to chip away at what was not needed, he would later state, so that David, tense, concentrated, and poised in the moment just before toppling Goliath, might step from his giant marble home.

I'd been researching for two years before meeting my narrator for Beware Madame la Guillotine, Charlotte Corday. By then I had read everything, attended every guided visit and lecture, and visited every monument and location related to French Revolution that I could. One day, while wandering through the birthplace of the Revolution, the Palais Royal, for the umpteenth time, I came upon a chalk picture portrait of dear Charlotte. Suddenly, it was as if she'd reached through the ages. She grabbed me by the lapels and begged me to let her tell her story as she had never been allowed to in life.

Once Charlotte had taken hold of my imagination, and my pen, and thanks to my now encyclopedic knowledge of her place and moment in time, I was confident enough to strike my first blow. Charlotte easily sloughed off her bonds and stepped out of history and onto the pages of my future app and interactive book. Her story indeed told itself.

From from our hotel roof terrace of Brunelleschi's dome.